18 Aug Building an eConsult System From Scratch – The 80s Way

The e-consult Pioneers & Leaders series takes a deeper dive into the history of e-consult by targeting its birthplace—the visions and motivations of those who started it all. In a succession of interviews with healthcare innovators who pioneered or contributed to e-consult initiatives, we untangle the e-consult system’s conceptual roots and purpose, crystallize its trajectory, and map the future potential of e-consult in healthcare settings.

It is 1988 in Apeldoorn, Netherlands when a bright-eyed PhD student joins forces with physicians to make some serious steps to improve care coordination in the region. Those steps, as it turns out, spelled the inklings of the process nowadays called “electronic consultation” (e-consult) between primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists.

Thirty plus years ago, Dr. Peter Branger was eager to merge his medical training with a newfound passion and academic pursuit in informatics. Incoming requests from a group of sixty PCPs for the doctoral student’s help to enhance care coordination processes presented Dr. Branger with a timely opportunity to merge his interests in the two scientific branches into a constructive body of work. Two champion PCPs who served as spokespeople for their larger group recognized the power in digitization of health information, thus reaching out to Dr. Branger as lead program manager for Erasmus University Rotterdam’s medical informatics division. Soon thereafter, Dr. Branger began to coordinate with the physicians to collect their grievances and find a solution via medical informatics.

“The general practitioners and the specialists talked to each other and realized ‘we are not cooperating or communicating in the right way,’” Branger remarked. “What I did in my pioneer work is start from this real medical question and facilitate from there.”

To briefly put the Dutch healthcare system into perspective: All patients in the Netherlands must mandatorily visit a PCP and obtain a referral before going to see a specialist in-person. In a system where referrals are necessary to see a specialist, poor coordination between PCPs and specialists often results in negative outcomes for patients needing to obtain care—such as prolonged wait times, repetitive procedures, and other inconveniences.

“I’ve heard from people around me, my own family, that when they visit the hospital, the specialist often has not the faintest idea what the general practitioner has done,” Branger said. “Within a few years the patient will not accept that anymore.”

As Branger ventured to hospitals to speak with various PCPs, he discovered it was not uncommon for PCPs and specialists to be unaware that they were seeing the same patient for the same issues. Black holes are not, per say, unique to outer space. Branger touched on a widespread problem that has plagued clinical communications and hindered effective care coordination for centuries—the black hole of PCP-to-specialist communications.

Branger’s task, then, consisted of essentially plugging up this black hole. By repurposing one of the first standardized message systems, known as Electronic Data Interchange for Administration, Commerce and Transport (EDIFACT), Branger and a team at the university developed a platform through which doctors could exchange clinical information. With financial support from an insurance company, the project involved coordination between Dr. Branger, an IT company, a group of sixty PCPs, and four specialists working across two regional hospitals in that region.

Together, they visualized and created an electronic communication module attached to a medical record system of the PCPs, as well as a communication portal for internists at the hospital to exchange data about shared patients—both from scratch. Branger said he first developed the information system with chronically ill patients in mind. People with diabetes or cancer, he reasoned, were bound to visit more than one PCP, as well as pay more frequent visits to specialists.

For instance, if a PCP met with a patient who had diabetes who also obtained treatment from a hospital, the results of that PCP-to-patient consultation were sent to that hospital and integrated into the specialist’s medical records. This meant that when the patient saw the specialist afterwards, the specialist would see what happened during the patient’s visit to the PCP’s office. Additionally, the specialist had the ability to contact the PCP about treatment or diagnosis for the patient with diabetes patient, using the same electronic communication system.

Forging ahead in medical informatics during the pre-internet, pre-email, and pre-electronic data interchange era was no easy feat, as you could imagine. Branger said one of the heaviest lifts of the initiative was not so much about people but more about technical maneuvers.

“Our team did a lot of programming and a lot of actual software support. Even on Christmas Eve I had to drive to the hospital to help out with a technical problem,” Branger chuckled, reminiscing. “But it was so much fun. Looking back at my career, this was one of the most exciting times in my work.”

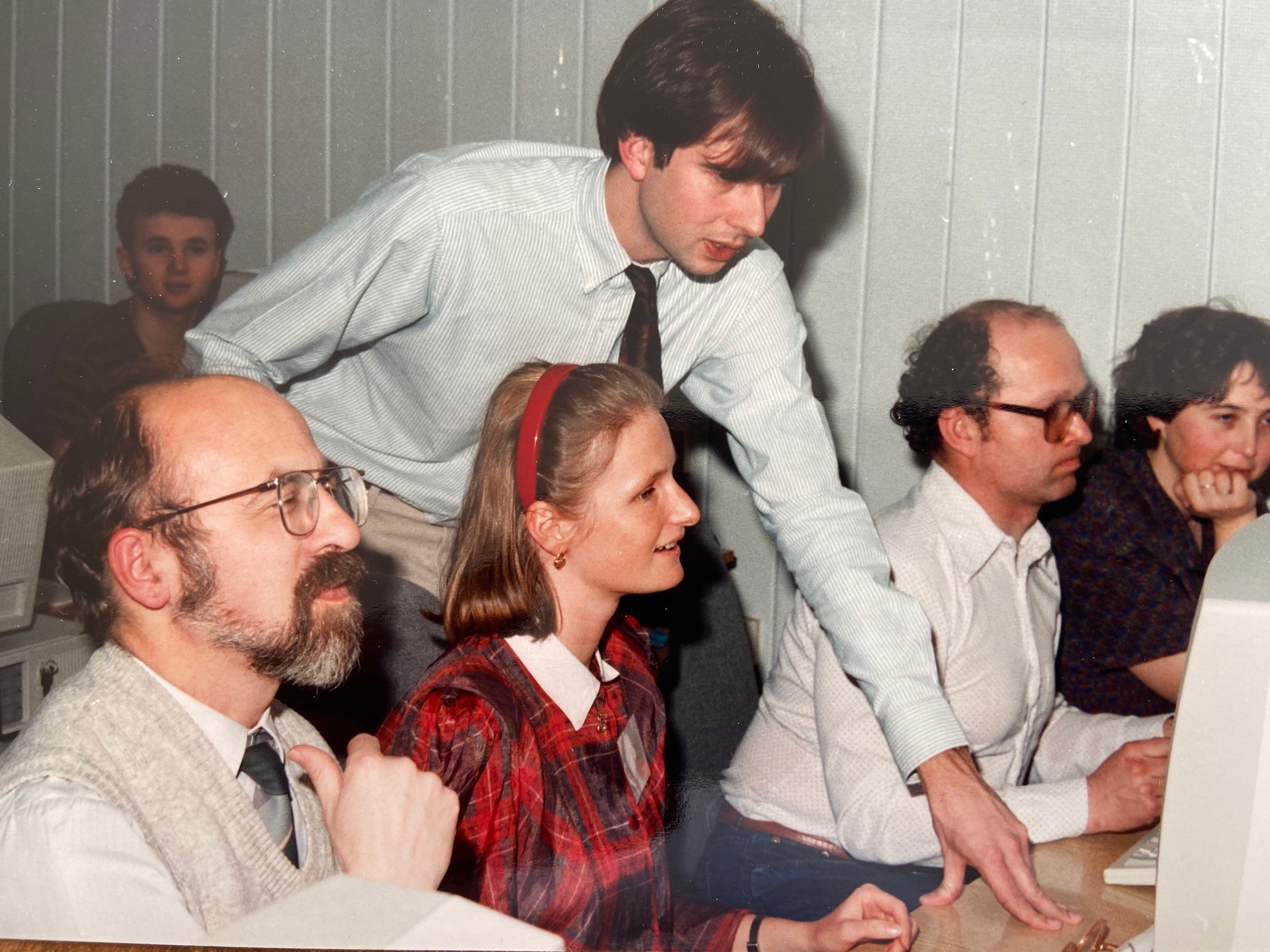

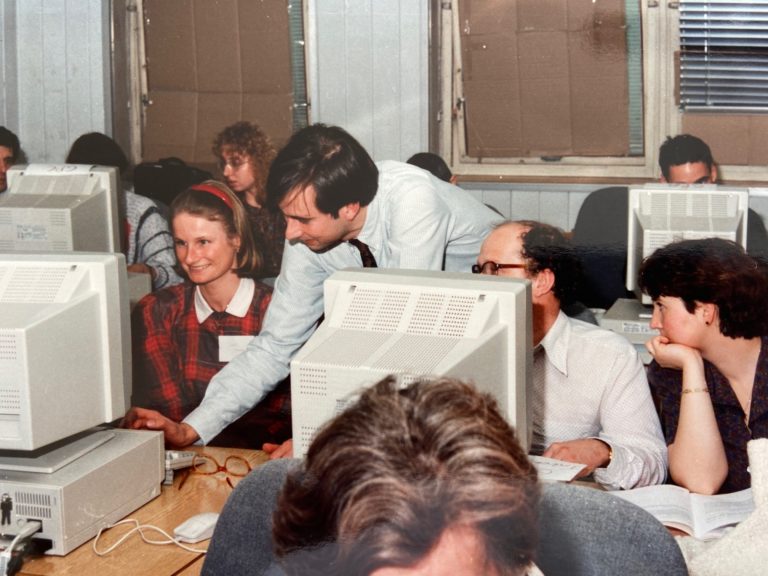

Caption: Peter Branger educating physicians in Prague about the use of electronic data interchange between primary care and specialty care.

Though technical capabilities have significantly improved since the late 1980s, healthcare continues to struggle with similar issues of ensuring solid channels for data interchange, as well as communication between PCPs and specialty care, he observed.

The expansion of PCP-to-specialist e-consult programs across the globe speaks to contemporary healthcare professionals’ and policymakers’ growing wills to rectify a longtime issue in care coordination. Though Dr. Branger’s pioneering efforts did not result in fully fledged e-consult processes in the way they are championed today—as care coordination and referral management tools—they certainly present important early steps in medical informatics. Based on the apt acknowledgement of the “black hole,” between primary and specialty physicians’ communications, these steps got the ball rolling on leveraging health information technology as a solution to alleviate barriers to efficient care coordination and continuity.

Given how much e-consult has developed as a concept and process since his pioneering efforts, Dr. Branger said he said he sees a future world of healthcare in which patients are not only directly involved in their health information, but are the keepers and controllers.

“If the patient can be the focal point of our efforts as physicians, then he or she can also be the one carrying his or her own data and be the center point of medical activities,” Dr. Branger said. “If the patient wants that, give him or her the tools give and empower him or her to engage in that communication with a physician. That’s the direction in which things are moving already.”

Read more about the project here

Dr. Peter Branger now serves as the General Director at Eurotransplant International Foundation.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.