The e-consult Pioneers & Leaders series takes a deeper dive into the history of e-consult by targeting its birthplace—the visions and motivations of those who started it all. In a succession of interviews with healthcare innovators who pioneered or contributed to e-consult initiatives, we untangle the e-consult system’s conceptual roots and purpose, crystallize its trajectory, and map the future potential of e-consult in healthcare settings.

In the world of healthcare, e-consults (short for electronic consultations) are commonly summarized as a secure virtual exchange between clinicians about a patient’s condition or medical question—imagine something similar to email for doctors!

Yet as I discovered through my conversation with Dr. George Bergus, a primary care provider at the University of Iowa, the early ancestor of e-consult proved to be actual emails between doctors.

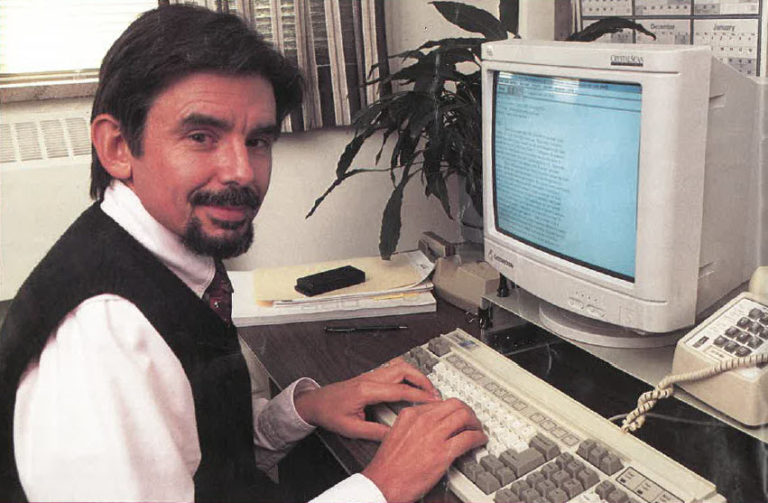

Let’s take a journey back in time—to the mid-nineties.

In 1995 Bob Kelch, Dean of the College of Medicine at the University of Iowa, urged Dr. Bergus to apply for a U.S. Public Health Service training grant which was intended to optimize training for physician residents. Dr. Bergus began to reflect on how to develop an educational service that would help residents learn by employing communication resources more efficiently.

Doctors were already well familiar with traditional curbside consults—informal meetings where family doctors could pick a specialist’s brain for advice or educational insight on a patient’s complex condition. When he served as a primary care physician at the Alaskan Native Health Center in rural Ketchikan, Alaska, Bergus utilized University of Washington’s telephone consultation service called MEDCOM to directly contact responsive specialists in Seattle. But this method of phone calls proved less effective when he tried again at University of Iowa.

“When I tried that same thing here at my medical school, you get put on hold, bounced around. It was a real time issue,” Bergus said.

What if there was a way to simulate this same pedagogic, clinical interaction between providers using asynchronous technology? Bergus summoned the power of email.

Come May 1996, the University of Iowa/Mercy Hospital Family Practice Residency Program secured $220,000 of federal funding to launch the E-Mail Consult Service (ECS). Together with the University Hospital’s IT experts Lee Carmen and Suzan Sinift, Bergus used Eudora software to craft a window/menu driven set-up. Here is how it worked: A primary care provider resident opened the software, selected a specialty from a drop-down menu, and typed up their clinical question. The inquiry would send from their computer to the hospital server which would identify and forward the email to a cardiologist consultant in the hospital.

It can be helpful to reminisce on the world of technology in 1996—one of CD-ROM textbooks and paper charts galore. Though it had been around since the seventies, email only just beginning to reach the masses twenty years later. On a good day, it was normal to receive a maximum of four emails, Bergus said.

In fact, Bergus recalled, “Most of us, the majority of the faculty, didn’t even have an email at the time.”

Once they received computers, modems and email accounts to engage with ECS, however, providers were able to sidestep disruptive attempts to catch a specialist in real time. The ECS model was voluntary and free-form, Bergus explained. There were few limitations: patient names or numbers were to be omitted for confidentiality, and specialist consultants were expected to respond within 24 hours. The simpler, the better.

“Somebody suggested we put text boxes in there to make sure people put in required information,” he said, “but we thought the more complicated we made it, the less likely people were to use it.”

And the goal was, after all, to encourage use. Bergus and his team arrived at interesting insights upon reviewing the content of dialogues along the way.

“We found that if the primary care doctor was willing to put their neck out and state what they thought was going on or what they thought they should do, the consultant was a lot less likely to ask to see the patient even the consultant thought the primary care doctor had the wrong plan,” he said.

Family practice residency trainees continued to make steady use of ECS for years to come, until email grew popular and inboxes began to explode. ECS proved no match for what Bergus dubbed the “email tsunami” of the early 2000s. Clinical inquires began float in a sea of other incoming mail, and federal funding ran out. On July 1, 2002 the University of Iowa dismantled the ECS server.

Thereafter, Bergus and colleagues monitored referral rates to outside specialists and noticed an increase. Dr. Bergus interpreted this trend as revelatory that family doctors in doubt with no convenient means of contacting a specialist for advice defaulted once more to making referrals.

Despite its eventual downfall, ECS was an early indicator of a movement in virtual care, one which eventually snowballed into today’s version of e-consult services.